This online exhibit explores the events of the Friendship Doll exchange program between the United States and Japan in the late 1920s. Miss Yamanashi is one of less than 50 dolls left in the world, and is a one-of-a-kind work of art.

Welcome

-

Introduction

This online exhibit explores the events of the Friendship Doll exchange program between the United States and Japan in the late 1920s. The Wyoming State Museum received the doll below, Miss Fujiko Yamanashi, as part of the program. Select the headers above to explore the events leading up to, during, and after the program.

This online exhibit explores the events of the Friendship Doll exchange program between the United States and Japan in the late 1920s. The Wyoming State Museum received the doll below, Miss Fujiko Yamanashi, as part of the program. Select the headers above to explore the events leading up to, during, and after the program.

U.S. Involvement

U.S. Involvement

U.S. Immigration Laws

In the late 19th century, U.S. industries needed laborers. They originally had hired Chinese workers, but in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was signed, preventing Chinese from entering the U.S. for a ten-year period. Because of this new law, labor recruiters began seeking Japanese workers instead.

On the West Coast, anti-Asian sentiments were rising. Tensions culminated in the Pacific Coast Race Riots of 1907 when Californians violently attacked Japanese immigrants and sparked riots along the West Coast and into Canada. The U.S. and Japanese governments met and established the 1907 Gentlemen's Agreement – Japan would no longer send new laborers to the U.S., and the U.S. agreed to quiet the unrest.

However, anti-Asian sentiment didn’t end there. The U.S. later passed the Immigration Act of 1924 which banned immigration from Asian countries.

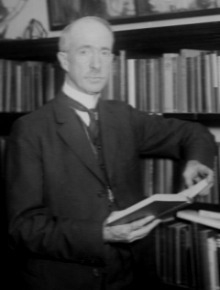

Rev. Sidney Gulick & the Committee on World Friendship Among Children

American sentiment towards Asian immigrants remained hostile into the 1920s. After passing the Immigration Act of 1924, Reverend Sidney Gulick wanted to repair the relationship between the U.S. and Japan. He had served as a missionary in Japan for 25 years and sought to ease cultural tensions through the children of both nations.

Gulick helped form a group called the Committee on World Friendship Among Children (CWFCA) through his connections with religious organizations. They agreed “that it is through education and in no other way that peace [between nations] will come…all children should be given the opportunity to become acquainted with the lives of children of other countries, to learn something of their habits, their costumes, their schools, their holidays, their language.”

The CWFCA sought to develop mutual cultural understanding through the children of the U.S. and Japan by initiating an exchange of children’s dolls. They decided to have dolls from the U.S. arrive by Hinamatsuri on March 3rd – Japan’s Festival of Dolls. Hinamatsuri is a holiday celebrated by Japanese, from the Imperial family to the lower classes, and was seen as a way to reach the most citizens.

What Did the U.S. Children Do?

Miss Georgia (left) and Miss Wyoming (right) were sent to Japan

Miss Georgia (left) and Miss Wyoming (right) were sent to Japan

The CWFCA began contacting churches, schools, and children's organizations across the U.S. to purchase dolls for the project. They required each doll to cost no more than $3 and be able to say ‘mama.’

The children also pitched in 99¢ for the doll’s traveling expenses, including a railroad ticket, steamer fare, and an additional railroad ticket once they arrived in Japan. Each doll came with a passport and a letter from the U.S. government ensuring their good behavior. Some children also included letters to accompany their dolls.

In total, over 12,000 dolls were sent to Japan.

Japan's Involvement

Japan's Involvement

Japanese Reception

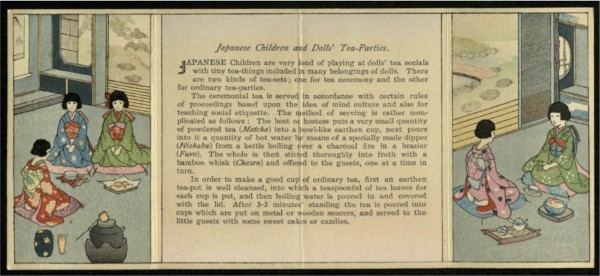

The dolls arrived in time for Hinamatsuri via steamer. On the docks, a group of Japanese girls welcomed them with a tea reception, and American girls officially gifted the dolls.

A grand reception was planned in March of 1927 in Tokyo. Japanese and American government agencies, dignitaries, and members of Japan’s aristocracy came to greet them.

Japanese dolls were placed on shelves customary to Hinamatsuri during the reception, and the American dolls were placed alongside them.

After the reception, the dolls were taken to Akasaka Palace for six days, where Japan’s empress and her infant daughter gave them an audience. They then went to Tokyo’s Educational Museum in a two-story dollhouse donated by the Empress.

The dolls were then distributed to each prefecture (county) in Japan along with a note from Gulick encouraging students to send a photo and note back to the U.S. of their respective dolls’ arrival.

Although the CWFCA and U.S. children requested nothing in return, the Japanese Committee of International Friendship and the Department of Education began plans for sending Japanese dolls to America.

Japan’s aristocracy led the effort, and each school that received an American doll was asked to donate one sen (less than $.01 in 1927) for new creations by the best doll makers in Japan. In total, 58 dolls and additional accessories were created and then returned to their respective prefectures for a farewell ceremony. Government officials and children attended these ceremonies, and the dolls received their steamboat tickets and passports to begin their journey across the Pacific.

Arrival in the U.S.

When the dolls arrived in San Francisco, the CWFCA organized a reception for them and a plan for a nationwide tour. After visiting the West Coast, Washington D.C., and New York, the dolls were separated into smaller groups to tour the rest of the U.S. They appeared at libraries, schools, churches, and various children’s organizations – most of these locations participated in sending the American dolls to Japan the previous year.

Since the program intended to educate the public and children about Japanese culture, the CWFCA thought “that an immediate placement of the dolls in permanent homes would be a serious disappointment, and would indeed prevent the little ambassadors from really delivering the goodwill messages that had brought…” A decision was made to distribute at least one doll to every state and preferably to children’s museums.

In Our Collection

After the dolls had finished their nationwide tour, a number of libraries and museums were gifted with a doll. The local Baptist Missionary Society was contacted by the Committee on World Friendship, asking if Wyoming would like to receive a doll.

Mrs. James W. Mason, acting for the Society, in partnership with Francis Birkhead Beard, the State Historian, arranged for a doll to be housed at the state museum at the capitol, and Wyoming was gifted with Miss Fujiko Yamanashi.

Miss Yamanashi came to the WSM with a passport, letters from schoolchildren, and a full bridal trousseau consisting of chests, a makeup stand, a mirror, a folding screen, a lantern, a tea set, a sewing kit, parasol, sandals, and a small purse.

A reception was hosted at the local Baptist church, with Japanese Americans joining the celebrations before Miss Yamanashi visited other local churches and schools.

World War II

Although the dolls’ purpose was to instill goodwill, the development of WWII and anti-Japanese and American sentiments hindered this cause in both countries.

In Japan, an edict forbade citizens to own any American dolls. Out of the 12,739 that were sent over, only 252 survived.

Likewise, many Japanese dolls were smashed or thrown away in the United States. Out of the 58 dolls sent from Japan, 27 survived.

Miss Fujiko Yamanashi

Miss Fujiko Yamanashi

The Wyoming State Museum received Miss Fujiko Yamanashi from the CWFCA program. She hails from, and is named for, the Yamanashi prefecture. Mt. Fuji is also located in Yamanashi. She may be one of the only dolls with a first and last name.

Miss Yamanashi is one of fifty-one friendship dolls made by the Yoshitoku Doll Company in Tokyo. These dolls have wooden-core torsos covered with fabric and hinged legs, allowing them to sit. They also have unique facial features sculpted using gofun - lightly pigmented crushed oyster shells. The dolls are about 32 inches tall, have human hair, glass eyes, and unique silk kimonos with symbolic details from their prefectures.

Miss Yamanashi’s kimono is purple, a noble color and the color of wisteria. In Japanese, fuji and wisteria are the same word with different pronunciations.

Over the years, the WSM has continued to care for and preserve Miss Yamanashi. You can learn more by clicking on the images below!

Chest of Drawers

Sewing Chest

Teapot

Tea Cups

Pouring Bowl

Cold Water Pot & Bamboo Whisk

Bulk Tea Container

Wicker Basket

Lamp with Silk

Metal Saucers

Black Lacquer Tea Caddies